CHAPTER V: USES OF PLANTS TO MAN

FOR perhaps the largest number of readers the chief value of plants is what they furnish in the way of food, clothing, fuel, and so forth, and from this standpoint alone the study of them is more than worth while. It is unnecessary here to enumerate all the thousand and one things that we get from plants, and no attempt will be made to do so in the following pages. But certain plants like wheat, corn, cotton, jute, rubber producers, and tobacco have so shaped the life of the people, so absolutely dictated the development of whole regions of the earth’s surface that their stories are part of the history of mankind. What our cotton fields of the South, the wheat and corn fields of the Middle West, the jute in India, and the coconut palm and sugar cane in the tropics have done to dictate the economic destiny of those regions is common knowledge. Hundreds of less important plants throughout the world contribute their quota to the huge debt that man owes to the plant world. Probably no other feature of plant life offers such attractions as the study of man’s uses of plants, which is known as Economic Botany, and for which our Government maintains a large staff of experts. Some of the publications of this bureau are textbooks of the greatest value to those who grow or import plants or their products. What that amounts to in the aggregate no one can readily estimate. It certainly exceeds all other commerce combined.

1. Foods

Those early ancestors of ours that roamed over northern and central Europe between the periods of ice invasion, which at times made all that country uninhabitable, tell us by the relics of them found in caves that agriculture was then unknown. Living mostly by the chase and on a few wild fruits picked from the forest these half-wild and savage people wandered wherever game was plentiful and the continental glacier would permit. But there came a day when one of these races began the cultivation of some of the wild plants about them and with that day dawned the real beginning of man’s use of plants. And with that day also these simplest of our ancestors stopped their wanderings in large part and became farmers, albeit very crude ones, as their primitive stone implements show. They did not give up the chase, but their collection into more or less permanent camps or villages began with their cultivation of plants. Just when this happened no one can say, but most estimates of the time since the last ice age indicate that it could not have been much less than forty thousand years ago. And considerably before this, and long before the use of metals by man, we find these stone implements of agriculture and the probable beginnings of that great reliance upon plant life which the modern world has carried to such tremendous lengths. Unfortunately we do not know what plants these “Men of the Old Stone Age” grew in their primitive gardens, and it is thousands of years after this, and after man’s discovery of the use of metals, that we know definitely what plants he grew and how he used them. Unquestionably some of the early uses of plants, such as dyes for the face or for “rock pictures” are very ancient and are found long before any sign of agriculture, but as food in the sense of being produced food rather than that gathered from the wild, there are only the faintest traces until, in the remains of the lake dwellers in Austria, a single grain of wheat was discovered. Their metal instruments showed them to have been familiar not only with this, but with other plants, and it is well to remember that these people lived far longer ago than our most ancient historical records such as the Egyptians or Chinese. Both the latter, so far as our oldest records of them show, were an agricultural people who had enormously developed man’s uses of plants as compared with the men of the stone or bronze ages, whose agriculture must perhaps forever be a secret of the past.

WHEAT

The discovery of the grain of wheat in the remains of the lake dwellers tells us some things about men’s travels even in those early days, for wheat is not a wild plant there and must have come to central Europe from a great distance. Researches upon the home and antiquity of wheat are not very definite, but its occurrence as a wild plant somewhere in Mesopotamia or the vicinity appears to be indicated. The Chinese grew it 2700 B.C. and the earliest Egyptians spoke of its origin with them as due to mythical personages such as Isis, Ceres, or Triptolemus. From its ancient and perhaps rather restricted home it has gone throughout the temperate parts of the earth and now forms perhaps the most important source of food. Although many different kinds of wheat are raised in different parts of the world most of them have been derived from one wild ancestor, Triticum sativum. Forms known as hard and soft wheat and dozens of others suited to different regions or market conditions have been developed by plant breeders. As the most important of all the cereals it has been much studied, and its cultivation in America is on such a tremendous scale that we furnish a large part of the world’s supply. Russia, Argentina, and the southern part of Australia also raise large quantities. The plant is a grass and the “seed” is really a grain or fruit in which the outer husk tightly incloses the true seed.

It were perhaps well to note here that popular stories about the germination of grains of wheat taken from Egyptian mummies are not true. Wheat and even corn are sometimes given to travelers, and it is taken from these ancient Egyptian tombs. But it was not put there by the early Egyptians, as the presence of corn proves only too well. For this cereal is an American plant unknown before Columbus and 1492. Arabs and others have recently inserted various seeds in these mummies, some of which undoubtedly have germinated—hence the fable. The early Egyptians did put seeds in their mummy cases, but none have ever germinated.

INDIAN CORN OR MAIZE

The grass family furnishes this second most important cereal to all Americans and Europeans, although among inhabitants of tropical regions rice is perhaps more important than either wheat or corn. With the discovery of America the early travelers found the North American Indians, the Mexicans, and the Peruvians all growing corn and using it on a considerable scale. It must have been grown for hundreds of years before that time, as its wide distribution and many varieties testified even at that date. Its true home nor its actual wild ancestor has never been certainly determined, but a wild plant very closely related to our modern corn is found in the northern part of South America, and either there or in Central America is apparently the ancient home of corn. So much had corn entered into the life of the early Mexicans that the first Europeans to visit that country found the Mexicans making elaborate religious offerings to their corn goddess. And, as in Egypt, the tombs of the Incas of Peru contain seeds of the cereal most prized, which in the case of corn consists of several varieties. While their civilization is not as old as certain Old World races, the cultivation of corn must date back to the very beginnings of the Christian era. It is now spread throughout the world in warm regions, and as early as 1597 it was grown in China, a fact that led to the erroneous notion that China was its true home. Perhaps no fact is more conclusive as to its American origin than that corn belongs to a genus Zea, which contains only the single species mays, with perhaps one or two varieties, and that until the discovery of America Zea mays or Indian corn was unknown either as a wild or cultivated plant. Such an important cereal, if it actually were wild in the Old World, would have spread thousands of years ago as wheat did, and Columbus and his adventurous successors would not have brought from the New World a food that has since become second only to wheat.

Field corn of several different sorts, pop corn, and sweet corn were all developed by the Indians from the ancient stock, but comparatively recently the juice of the stem has been used for making corn sirup. The use of the leaves for cattle feed is known to all farmers, and from its solid stems it is now likely that some fiber good for paper making will be extracted.

RICE

Both wheat and corn are grasses that are cultivated in ordinary farm soils, but rice is derived from a grass that is nearly always grown for part of its life in water. It is taller than wheat, but not so tall as corn, and its wild home is in the tropical parts of southeastern Asia. It is still grown there in greatest quantity, and in the Philippines, while only a small part of the world’s supply comes from the New World. There are perhaps more people that rely upon rice for food than upon wheat and corn combined. It still is the principal article of diet of the inhabitants of China, Japan, India, and dozens of smaller Old World regions, while its use as a vegetable in tropical America is practically universal. A considerable part of the starch manufactured in Europe still comes from rice, and in India the intoxicating beverage arrack is made from it. The Japanese saké, a sweetish intoxicating liquor, is also made from rice. Notwithstanding its wide use it is not as nutritious as wheat or corn, being much lower in proteins than either of them.

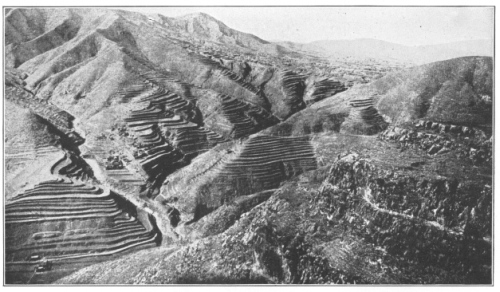

More than 2800 years before Christ the Chinese cultivated rice, for at that time one of the emperors instituted a ceremony in which the grain plays the chief part. It has been grown on land useful to almost no other crops as it is usually subject to inundations. Some varieties, however, have been developed which will grow on uplands and these are grown even on terraced land both in China and the Philippines. It needs a heavy rainfall, however, and grows best in lands that are flooded. It is occasional dry seasons that produce the famines of India when the crop fails. The botanical name of rice is Oryza sativa, and it is known now as a wild plant in India and tropical Australia. Its introduction into Europe must have been long after wheat, for rice is not mentioned in the Bible, and was unknown in Italy before 1468, when it was first grown near Pisa. Rice paper, which some people think is made from this grain, comes from the pith of Aralia papyrifera, a tree of the rain forests of Formosa, related to our temperate region Hercules’-club.

SUGAR

In the chapter on what plants do with the material they take from the air and soil we found that sugar was one of the first fruits of that process. In at least two plants the overproduction of sugar is on such a great scale that our chief supplies of this substance now come from these two plants—the sugar cane, which is a tall grass, and the sugar beet. Hundreds of other plants produce surplus sugar, but for commercial purposes these two, and the sap of the sugar maple (Acer saccharum), are our chief sources of supply.

Cane sugar is an Old World grass known as Saccharum officinarum, frequently growing twelve feet high, and with a solid woody stem, quite unlike our ordinary grasses. It looks not unlike corn on a stout stem, and it is the stem which is cut and from which the sweet juice is pressed out between great rollers. The pressed-out juice goes through various processes in the course of which first molasses, then brown sugar, and finally white granulated sugar are produced.

Our consumption of sugar is now on such a scale that we scarcely realize that before the days of Shakespeare it was very scarce and expensive. Even as recently as 1840 it regularly sold in England for forty-eight shillings per hundred pounds, wholesale. At that time the total consumption in the world was only slightly over a million tons, while to-day it is over fifteen times that amount. The plant is native in tropical Asia, but just where is not known, nor are wild plants found in any quantity. It has been much modified by long cultivation, and has been reproduced by root-stocks for so long a period that it is rare for the plant to bear flower and seed. It has been known in India since before the Christian era, and was taken from there to China about 200 B. C. Neither the Greeks nor Romans knew much about it, nor do the Hebrew writings mention it. Somewhere in the Middle Ages the Arabs brought it into Egypt, Sicily, and Spain. Not until the discovery of the New World was it cultivated on any considerable scale, when the climate of Santo Domingo and Cuba and the African slaves imported to those islands afforded conditions that resulted in Cuba at least being one of the world’s chief sugar-producing countries. Sugar cane is now grown all over the earth in regions with a hot, moist climate, India and neighboring countries producing over half the world’s supply. Practically all the sugar produced in India is used there, however, so that the American tropics furnish to Europe and America about one-third of the world’s total consumption of cane sugar.

In 1840 under fifty thousand tons of beet sugar were produced, while in 1900 more sugar from this plant was made than from sugar cane. Considerably more than half this beet sugar was grown in three countries, Russia, Austria, and Germany, which explains what the great war has done to the sugar market. The plant from which beet sugar is derived is botanically the same as the common garden beet, Beta vulgaris, which is wild on sandy beaches along the Mediterranean and Caspian seas, and perhaps in India. Much cultivation has made this slender-rooted plant into the large-rooted vegetable we now have and its sugar content was much increased by Vilmorin, a French horticulturist. Many garden varieties are known, and some of these are grown in the United States, where beet sugar is produced, although in 1910 less than half a million tons were made here as against over four million tons in Europe. While the beet as a vegetable was known perhaps a century or two before the time of Christ, it was not until 1760 that its sugar content was understood, and it was nearly eighty years later before beet sugar became commercially important. Its cultivation in England on any considerable scale did not begin before the beginning of the present century.

THE BANANA

Among the largest herbs in the world are the ordinary banana plants, now cultivated throughout the tropical regions, but originally native in the Malay Archipelago. From there it spread into India, and the early Greeks, Latins, and Arabs considered it a remarkable fruit of some Indian tree. It is actually a giant herb with a tremendous fleshy stem, formed mostly of the tightly clasping leaf bases, the blade of which is frequently ten to twelve feet long. In nature the blade splits into many segments due to tearing by the wind, a process that the plant not only tolerates but aids. The leaf has a thinner texture between its principal lateral veins, and along these weaker parts the leaf tears so that normal plants are usually almost in ribbons. The leaf expanse, without this relief, is so great that tropical storms would doubtless destroy the plant.

Many wild species of the banana are still found in tropical Old World countries, the genus Musa to which the banana belongs having over sixty-five species. There are at least three well-marked types of banana used to-day, two of them, our common yellow one and a smaller red sort being fruits of almost universal use. The remaining type is usually larger than the kinds sent to northern markets, is picked and used while still green and is always cooked before using, usually boiled as a vegetable. In this form it is known as the plantain, and is a good substitute for the potato in regions where the latter cannot be grown. Plantains are used on a large scale in all tropical countries, much more so than the yellow and red bananas which are familiar enough in northern markets. These are too sweet to be used as a staple diet, and the plantain is practically the only such diet which millions of the poorer people in the tropics ever get. There is almost no native hut but has its plantain field.

The flowers of the banana plants, all of which appear to be derived from the single species Musa sapientum or possibly also from Musa paradisiaca, are borne in a large terminal cluster which ultimately develops into the “hand” of bananas familiar in the fruit shops. The plant then dies down and a new one develops from a shoot at the base of the old stem. For countless ages this has been the only method of reproduction, and usually the banana produces no seeds. The plant is easily grown in greenhouses, one in the conservatory of the Brooklyn Botanic Garden producing 214 pounds in a single cluster consisting of 300 bananas.

POTATO

Sir Walter Raleigh is usually credited with the introduction of the potato into Europe, although it appears as though the Spaniards were the first to bring the plant from America. It was brought to Ireland in 1585 or 1586 and from its wide use there became known as the Irish potato. Its native home is in southern South America, and although Columbus did not mention it after his first and second voyages, subsequent Spanish adventurers found natives on the mainland making extensive use of it. There are now several wild relatives of it in South America, but their tubers are not so large as those of Solanum tuberosum from which all the different varieties of potato have been derived. The plant is too well known to need description here, but its edible tuber, actually a stem organ, is often wrongly called a root. Figure 8 shows the tubers and true roots of the plant.

The sweet potato, which in early writings was often confused with Solanum tuberosum, is a very different plant. Its edible portion is the root of a vine very like our common morning-glory or convolvulus, and its Latin name is Ipomœa batatas. The specific name is taken from a native American word, which due to early confusion was corrupted into potato, and applied to the “Irish” potato. No one certainly knows where the sweet potato is native, but probably in tropical America. It belongs to a section of the genus Ipomœa, all the other species of which are American, and before Columbus and his followers its cultivation was unknown in the Old World. It was very soon carried by the Portuguese to Japan and other parts of the Old World, and for a time it was thought to be native there. America, however, is in all probability its ancient home, although no really wild plant has ever been found there or anywhere else. Its cultivation from very early times in America is indicated, and Columbus upon his return from the New World presented sweet potatoes to Queen Isabella.

COCONUT

It has been said many times that there are more uses for this plant than there are days in a year. Wood, thatch, rope, matting, an intoxicating beverage, and scores of other things are derived from different parts of this palm, but it is as a food and beverage that its chief value lies. The coconut palm is a tall tree with a dense crown of feathery but stout leaves and inhabits all parts of the tropics. It is found apparently wild along sandy shores, but its ancient home, while still unknown, is probably America. Each year the tree bears from ten to twenty fruits which are at first covered with a green and very tough fibrous husk, inside which is the seed, the coconut of commerce. In the early stages of the fruit the white meat is preceded in large part by a delicious milky liquid much used by the natives, but only rarely found in any quantity in the coconuts shipped to our markets. The meat is highly nutritious and is used on a great scale as food by millions of tropical peoples. Within the last few years a method of taking out the meat of the coconut and shipping it in a state of arrested fermentation to the north has been discovered. This product, known as copra, is produced in enormous quantities, both in the Old and the New World, particularly in India and the Philippines. From this copra a palm oil is refined, which is the chief source of the nut butter now so widely sold. Some idea of the extent of the cultivation of coconuts may be gleaned from the fact that in India and the Philippines the trees are counted by the hundreds of millions. The oil from the nuts is also largely used in cookery, in making candles, for burning in lamps, and in making certain kinds of perfume. The tree belongs to the Palmaceæ, a monocotyledonous family of plants of great commercial importance. It is known as Cocos nucifera, and the genus has over a hundred species, all of tropical American origin. Whether Cocos nucifera is American or not is still a disputed point. From the fact that it will float in sea water without injury to the seed it has been supposed that it was carried great distances by currents. It is found both wild and cultivated throughout the tropical world, and its use appears to have been known to the Asiatics probably four thousand years ago. The curious fact remains that it is the only palm that, in its wild state, is known both in the Old and New World, all others being peculiar to one hemisphere or the other. Perhaps its capacity for floating in the sea without injury may explain what is otherwise still a good deal of a mystery.

There are many other foods derived from plants, besides all the fruits and vegetables too numerous to be noted in detail here. One fact of significance seems to stand out from a study of the uses of plants by man. There are three distinct regions from which the great bulk of our food and many other useful plants have apparently come. One is the area of which Indo-China is approximately the center, and which is the ancestral home of rice, the banana, tea, sugar cane, and many other valuable plants. Somewhere in this southeastern corner of Asia there must have been a highly developed agriculture which rescued these plants from the wild, and from which they have spread throughout the world. The second region, somewhere near Mesopotamia, appears to be the cradle of wheat and a few other useful plants. And the third region is the western part of America from southern Mexico to northern Chile, where corn, tobacco, the pineapple, sweet potato, potato, the red pepper, and the tomato were all discovered with the discovery of this continent.

Alphonse de Candolle, from whose studies much of our information on the origin of cultivated plants is derived, once prepared a list of our common vegetables showing their ancient homes, their wild ancestors, and the length of time during which they have been in cultivation. With some recent additions and corrections by Dr. Orland E. White of the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, the list is printed below:

The letters indicate the probable length of cultivation.

(a) A species cultivated for more than 4,000 years.

(b) A species cultivated for more than 2,000 years.

(c) A species cultivated for less than 2,000 years.

(d) A species cultivated very anciently in America.

(e) A species cultivated in America before 1492 without giving evidence of great antiquity of culture.

(f) A species or subspecies of very recent domestication.

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Date | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Artichoke, Globe | Cynara Scolymus L. | C | Southern Europe, northern Africa, Canary Islands. |

| Artichoke, Jerusalem | Helianthus tuberosus L. | E | Eastern North America. |

| Asparagus | Asparagus officinalis L. | B | Europe, western temperate Asia. |

| Bean (Broad or Windsor) | Vicia Faba L. | B(?) | Temperate Europe. |

| Bean (Pole Lima) | Phaseolus lunatus L. | E | Tropical America, Peru, Brazil. |

| Bean (Bush Lima) | Phaseolus lunatus L. | F | Eastern North America. |

| Bean (String, etc.) | Phaseolus vulgaris L. | D | Western South America. |

| Bean (Tepary) | Phaseolus acutifolius Gray | D | Southwestern United States. |

| Bean (Adzuki) | Phaseolus angularis Willd. | (?) | China, Japan. |

| Beet (Chard) | Beta vulgaris L. | B | Canary Islands, Mediterranean region, western temperate Asia. |

| Beet (Root) | Beta vulgaris L. | B | Europe, Mediterranean region. |

| Broccoli | Brassica oleracea var. botrytis DC. | C | Western Asia. |

| Brussels sprouts | Brassica oleracea var. gemmifera DC. | C | Belgium (?) |

| Cabbage | Brassica oleracea L. | A | Western Asia. |

| Cabbage (Chinese) | Brassica Pe-tsai Bailey | B | China, Japan. |

| Carrot | Daucus Carota L. | B | Europe, western temperarate Asia. |

| Cauliflower | Brassica oleracea botrytis DC. | B | Western Asia. |

| Celeriac | Apium graveolens L. var. rapaceum DC. | C | Europe. |

| Celery | Apium graveolens L. | B | Temperate and southern Europe, northern Africa, western Asia. |

| Chives | Allium Schoenoprasum L. | C | Temperate Europe, Siberia, northern North America. |

| Corn (field) | Zea Mays L. | D | Mexico, northwestern South America (?) |

| Corn (sweet) | Zea Mays saccharata Sturt. | E | Eastern North America, New England. |

| Cress (garden) | Lepidium sativum L. | B | Persia (?). |

| Cress (water) | Radicula Nasturtium-aquaticum L. | B | Europe, northern Asia. |

| Cucumber | Cucumis sativus L. | A | India. |

| Cucumber (gherkin) | Cucumis Anguria L. | F | West Indies. |

| Dandelion | Taraxacum officinale Webe | C | Europe and Asia. |

| Egg plant (aubergine) | Solanum Melongena L. | A | India, East Indies. |

| Endive | Cichorium Endiva L. | C | Mediterranean region, Caucasus, Turkestan. |

| Garlic | Allium sativum L. | B | Kirghis desert region in Siberia. |

| Horse-radish | Roripa Armoracea L. | C | Eastern temperate Europe, western Asia. |

| Kale | Brassica oleracea var. acephala DC. | B | Europe. |

| Kohl-rabi | Brassica oleracea var. Caulo-Rapa DC. | B | Europe. |

| Leek | Allium Porrum L. | B | Mediterranean region, Egypt. |

| Lentil | Lens esculenta Moench | A | Western temperate Asia, Greece. |

| Lettuce | Lactuca sativa L. | B | Southern Europe, western Asia. |

| Mushroom | Agaricus campestris L. | C | Northern hemisphere (Europe). |

| Okra (gumbo) | Hibiscus esculentus L. | C | Tropical Africa. |

| Onion | Allium Cepa L. | A | Persia, central Asia. |

| Onion (Welsh) | Allium fistulosum L. | C | Siberia, Kirghis desert region to Lake Baikal. |

| Parsley | Petroselinum Hortense Hoffm. | C | Southern Europe, Algeria, Lebanon. |

| Parsnip | Pastinaca sativa L. | C(?) | Central and southern Europe. |

| Pea (garden) | Pisum sativum L. | A | Western and central Asia, southern Europe, north India (?). |

| Pea (wrinkled garden) | Pisum sativum L. | F | England (?). |

| Pea (edible podded) | Pisum sativum var. saccharatum Hort. | C | Holland, etc. |

| Pepper (red) | Capsicum annuum L. | E | Brazil, western South America. |

| Potato | Solanum tuberosum L. | E | Chile, Peru. |

| Potato (sweet) | Ipomœa Batatas Poir. | D | Tropical America. |

| Pumpkin | Cucurbita pepo L. | E | Subtropical and tropical America. |

| Radish | Raphanus sativus L. | B | Temperate Asia. |

| Radish (Japanese giant or Daikon) | Raphanus sativus L. | ?) | Japan, China. |

| Rhubarb | Rheum Rhaponticum L. | C | Desert and subalpine regions of southern Siberia, Volga River. |

| Rutabaga | Brassica oleracea var. Napo-Brassica L. | C | Europe. |

| Salsify or Oyster plant | Tragopogon porrifolius L. | C(?) | Southeastern Europe or Algeria. |

| Spinach | Spinacea oleracea L. | C | Persia, southwestern Asia. |

| Spinach (New Zealand) | Tetragonia expansa Thunb. | F | New Zealand. |

| Squash (winter) | Cucurbita maxima Duch. | E or D | Tropical America. |

| Squash (summer) | Cucurbita Pepo L. | E | Temperate or tropical America. |

| Tomato | Lycopersicum esculentum Mill. | F | Peru. |

| Tomato (currant or raisin) | L. pimpinellifolium Dunal | F | South America. |

| Turnip | Brassica Rapa L. | A | Europe. |

| Yams | Several sp. including Dioscorea alata L. and D. Batatas Decne. | B (?) | Southeastern Asia, Africa and South Pacific Islands. |

The following list of the common fruits also gives their native country, period of cultivation, and some additional notes about them. Those marked with a star were found in the markets of New York City by Dr. White, who also revised this list. The letters for the dates are the same as in the list of vegetables:

| Name | Date | Origin | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Achocon | F(?) | Peru | Relative of the violet. Much esteemed locally. |

| *Actinidia | (?) | N. E. Asia, China | Tastes something like a gooseberry, with a fig flavor. |

| Akee | F | W. tropical Africa | Much esteemed cooked fruit in Jamaica. |

| *Alligator pear (avocado) | E | West Indies, W. South America to Chile | Excellent salad fruit. |

| Anchovy pear | West Indies | Unripe fruit pickled. | |

| *Apple | A | E. Europe, W. Asia | Very different type common to China |

| *Apricot | A | Central Asia, China | Wild species variable. |

| *Banana | A | Southern Asia | Exists in hundreds of varieties. |

| *Blackberry | F | United States | Wild species very variable. |

| *Blueberry | F | E. and N. North America | Four species. Often confused with huckleberry. |

| Breadfruit | (?) | East Indies | Baked and eaten as a vegetable. |

| Buffalo berry | F | N. W. United States | Very acid, bright red or yellow fruit. Local. |

| *Cactus fig | E | Mexico, West Indies | Common New York City fruit. |

| Cambuca | (?) | Brazil | Subacid garden fruit. Local. |

| Cashew | (?) | Tropical America | Fruit excellent as preserves. |

| *Cherry, sour | B | Asia Minor, S. E. Europe (?) | Locally common. |

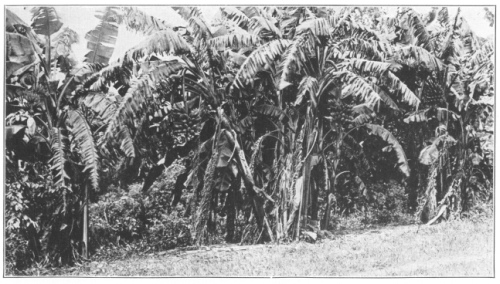

A Banana Plantation in Fruit. The banana is now grown throughout the tropical world, but native in tropical southeastern Asia. (Courtesy of Brooklyn Botanic Garden.)

Rice Terraces in China. In many regions where the forests have been destroyed and all the soil washed into the valleys, agriculture has to be carried on under conditions of great difficulty. Soil is brought up these slopes and held there by the artificially made terraces. (Photo by Bailey Willis. Courtesy of Brooklyn Botanic Garden.)

| Name | Date | Origin | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| *Cherry, sweet | B | S. Europe, E. Asia | N. Y. City markets from California. |

| Chirimoya | E | Ecuador, Peru | Repeatedly dug up from prehistoric graves in Peru. |

| Chupa-chupa | F | Colombia | Apricot-mango flavored. |

| Citron | B | India, S. Asia | Very variable. |

| *Cranberry | F | E. and N. North America | Cultivated for about 100 years. |

| *Currant, black | C | N. Europe and Asia | Rarely cultivated in America. |

| *Currant, red | C | N’th’n Hemisphere | White and yellow varieties are forms. |

| *Custard apple | (?) | Tropical America | |

| *Date | A | Arabia, north Africa | Hundreds of varieties. |

| Dewberry | F | South and central North America | Form of blackberry. |

| Duku | (?) | Malay Peninsula | Fine Malayan fruit, somewhat turpentine in flavor. |

| Durian | F | Malaysia, East Indies | Odor of old cheese, rotten onions flavored with turpentine. Delicious except for odor. |

| *Fig | A | Southern Arabia | Wild form common. |

| Genip | (?) | N. South America | Children’s fruit. |

| Genipap | (?) | American tropics | Used for a refreshing drink locally. |

| *Gooseberry | C | N. Europe, N. Africa, W. Asia, United States | Old and New World species distinct. New World varieties in some cases hybrids. |

| “Goumi” berry | (?) | Japan, China North America | Delicious acid fruit. |

| *Grape, New World | F | Western temperate | Many probably hybrids. |

| *Grape, Old World | A | Asia | California and Old World grape. |

| *Grapefruit | B | Malayan and Pacific Is., east of Java | Largely cultivated in U. S. |

| Ground cherry | F | Barbadoes, W. South America, Asia | Three or more species. |

| Grumixama | (?) | Brazil | Much like bigarreau cherry. |

| *Guava | E | Tropical America | Fruits of several species used. |

| Haw (2 species) | (?) | China, South United States | Local fruit. |

| Icaco | F (?) | Tropical America | Common fruit in San Salvador. |

| Jaboticaba | F | Brazil | Common fruit tree around Rio Janeiro |

| Jujube, common | B | China | Very excellent dried fruit in China. |

| Juneberry | F | United States, Canada | Locally esteemed. |

| *Kumquat | (?) | Cochin-China or China | Resembles very small oranges. |

| *Lemon | B | India | Largely used for limade and citric acid. |

| *Lime | B | India S. China, Malay | |

| *Litchi and relatives | C | Archipelago | Finest Chinese fruit. Numerous forms. |

| *Loquat | (?) | Central-east’n China | Much esteemed in China and Japan. |

| Lulo | F | Colombia | Tomatolike fruit. |

| Mammee apple | (?) | West Indies to Brazil | “St. Domingo apricot.” |

| *Mango | A (?) | India | “Should be eaten in a bathtub.” |

| Mangosteen | (?) | Sunda Islands, Malay Peninsula | King of tropical fruits. |

| Marang | (?) | Sulu Archipelago Mexico, N. E. | Similar to but much better than breadfruit. |

| Marmalade plum | E | Mexico, N.E. South America | Resembles in taste a ripe, luscious pear. |

| Matasano | E | Central America | “Delicious.” |

| Medlar | C | Central Europe to W. Asia | Local applelike fruit. |

| Monstera | F | Mexico | Pineapple-banana flavor. |

| Mulberry, black | B (?) | Armenia, N. Persia | Most valued for fruit. |

| Mulberry, white | A(?) | India, Mongolia | Most valued for feeding silk worms. |

| *Muskmelon | C | India, Beluchistan, W. Africa | Hundreds of varieties. |

| Natal plum | F | South Africa | Local fruit for preserves. |

| *Nectarine | (?) | Cultivated form of peach | Smooth-skinned. |

| *Olive | A | Syria, southern Anatolia and neighboring islands | Does not fruit in Florida. |

| *Orange, king | (?) | Cochin-China | Recently common in New York City markets. |

| *Orange, sweet | C | India | Numerous hybrids with other species. |

| *Orange, tangerine | ? | Cochin-China, China | |

| Papaw | F | South’n United States | Local fruit related to the custard apple. |

| Papaw, true | E | Tropical America | Excellent breakfast fruit. |

| *Passiflora | F (?) | Tropical America | Used locally for ices, fruit salads, jams, etc. |

| *Peach | E | China | Hundreds of varieties. |

| *Pear | A | Temperate Europe and Asia, N. China | Two species, and hybrids between them. |

| *Persimmon | (?) | Northern China | Common in New York City markets. |

| *Pineapple | E | American tropics. | Red Spanish and sugar loaf, common market varieties. |

| Piñuela | (?) | Mexico, C. America and N. South America | Sold cooked in Mexico. Common market fruit of Caracas. |

| *Plantain | Form of banana. | ||

| *Plum | A | S. Europe, W. Asia, N. America | Much hybridized group. |

| *Pomegranate | A | Caucasus, Persia, Afghanistan, Beluchistan | A seedless variety is known. |

| *Quince | A | Persia to Turkestan Middle N. America | “Apple of Cydon” (Crete). |

| *Raspberries, black | F | Locally much esteemed American fruit. | |

| *Raspberries, red | C | N. Europe, Asia, N. America | Varieties and hybrids of two species. |

| Rose apple | B | Malaysia, S. Asia | Rose-water taste and perfume. |

| Rose apple relatives | Tropics of Old and New Worlds | Many promising local fruits. | |

| *St.-John’s-Bread | A (?) | Syria, S. Anatol Barca (?) | Common dried pod fruit in New York City. |

| Sand cherry | F | N. W. United States | Local fruit. |

| *Sapodilla | E | West Indies, Central America, N. South America | “Chicle” or chewing gum made from its sap. |

| Sapote, black | F | Mexico | Relative of persimmon. |

| Shaddock | B | East Indies | Large pyriform relative of grapefruit. |

| Soursop | (?) | West Indies | Locally esteemed. |

| Star apple | E | W. Indies, Central America | Delicious. “Damson plum.” |

| *Strawberry | F | Temperate N. America, Pacific coast of N. and S. America, Europe Bush veldt of South | At least three species involved. Mostly hybrids. |

| Strychnos apple | F | Africa. | Tastes like clove-flavored pears. |

| *Sweetsop | (?) | West Indies | Locally esteemed. |

| Tahiti apple | (?) | Society, Friendly, Fiji Islands South America | Common tropical fruit. |

| Tahiti apple relatives | (?) | Common West Indian fruit. | |

| *Tamarind | B (?) | Either India or N. Africa | Occasional New York City fruit. |

| “Tomato,” tree | (?) | Peruvian Andes | Apricot-flavored tomato. |

| *Watermelon | A | Tropical and South | Often a desert plant. |

2. Beverages

The operation of the Eighteenth Amendment to our Constitution will stop the manufacture in this country of the chief beverages that were made here from plants. All wines and brandies were from the juice of the grape, whiskey from rye and some other cereals, and beer from hops and barley. Our three remaining beverages of practically universal use are none of them produced in the United States, with the exception of a little tea grown in a more or less experimental way.

TEA

It is related in an old legend that a priest going from India into China in 519 A.D. who desired to watch and pray fell asleep instead. In a fit of anger or remorse he cut off his eyelids which were changed into the tea shrub, the leaves of which are said to prevent sleep. Unfortunately for the story tea was known in China more than three thousand years before the date of that legend, and it is very doubtful if it was ever brought from India to China. The wild home of the tea is apparently in the mountainous regions between China and India, but the plant will not stand the frost, so that its cultivation is now mostly in parts of China, Japan, India, Ceylon, Java, and some in Brazil.

The plant is mostly a shrub or occasionally a small tree, with white fragrant flowers and evergreen oval-pointed leaves. All the different kinds of tea are derived from the single species Camellia Thea, the differences in color and flavor being due to processes of culture or curing of the leaves.

FIG. 99.—TEA (Camellia Thea) A shrub or small tree with white fragrant flowers.

FIG. 99.—TEA (Camellia Thea) A shrub or small tree with white fragrant flowers.

While the use of tea has been known to the Chinese for over four thousand years, its introduction into Europe dates from the days of the Dutch East India Company, who brought some to Holland about 1600, and by the English East India Company, who sent some from China to England in 1669. It fetched at that time 60 shillings per pound for the common black kinds and as much as £5 to £10 per pound for the finer kinds. It was almost fifty years, or about 1715, before the price fell to 15 shillings per pound. From that time until the present there has been a tremendous increase in its use, although then as now the great bulk of the world’s tea is used by the Mongolians and Anglo-Saxons. Just before the war over 700 million pounds comprised the annual crop of tea. As its use became general the English put a tax upon its importation into Great Britain or its colonies, with results here that we all know.

The cultivation of tea is restricted to those regions where there is a large and frequent rainfall as well as a high temperature. It will not grow in marshy places such as rice prefers, but needs light, well-drained soils. The plant is propagated only from seeds which are sown in nurseries, and the young plants set out in the tea fields about four and a half feet apart each way. In two years they are bushes from four to six feet tall when they are cut back to a foot high. The increased vigor of the bush from this severe cutting back results in a dense bush, from which leaves are plucked from the third year in small quantity. Not until after the sixth or seventh year is there a normal yield, which in an average year would be from four to five ounces of finished tea. A poor yield of leaves would average about 400 pounds of tea per acre, good yields going as high as a thousand pounds or even more than that. The tea fields must be kept free of weeds, a tremendous task in a moist tropical region, which demands cultivation about nine times a year. The expense of properly setting out and maintaining a tea plantation is therefore considerable.

The plucking of tea leaves is a fine art beginning with the starting of new growth and continuing every few days until growth stops. In certain regions growth is practically continuous and plucking also, but in most regions the plant has an obvious resting period, when it is pruned back. A properly cared for plant may last as long as forty or fifty years. In a modern tea plantation the only part of the process of tea making that involves handling is the plucking of the leaves, largely done by women and children. The leaves are then spread on racks and allowed to partly wither, after which they are put between rollers so as to crush the tissue, thereby allowing the more rapid escape of water. After rolling, all black teas are again spread out when oxidation of their juices changes their color, but green teas omit this second spreading out and sometimes even the first. The oxidation of black teas is produced by an enzyme in the juice, in green tea this process is stopped by subjecting the leaf at once to steam. This kills the enzyme but preserves the green color of the leaf. In the black tea the enzyme is allowed to work for two or three hours when the leaves are again slightly rolled to seal in the juices and the leaves are then subjected to a current of air progressively warmer until it reaches a temperature well above boiling point. Once the temperature reaches about 240 degrees the process goes on only for about twenty minutes when the leaves are perfectly dry and crisp. The different sized leaves, buds, twigs, etc., are then sorted by mechanical sifters and the finished tea is ready for packing. Experts declare that there is no difference between broken and unbroken leaves, and if there is any the flavor is probably better from broken leaves. From the upper three leaves and their bud the finest teas are made, but from adjoining plantations, even from the same plants at different seasons or different pluckings, vastly different teas are often produced. In different regions the process varies slightly in its details, and different soils and culture undoubtedly affect the flavor of tea, just as they do other crops. Some of these local conditions are of great value, and the skillful handling of the leaves is as much of a fine art as it is a science. Unlike wines, tea is best when fresh and much of the romance of the sea centers around the China clippers which made remarkably swift passages between China and England around the Cape of Good Hope. With the opening of the Suez Canal competition for increased speed became still more keen, but steam vessels took the romance out of the trade. Much of the tea used in the United States comes from Japan and does not go through London, which for over two hundred years was the tea market of the world.

The thing for which we drink tea is an alkaloid in its leaves that is pleasant to the taste and refreshing to the senses. It is released in boiling water in a very few minutes, but if tea is allowed to stay in water longer than this, tannic acid is also released. This is a substance found in the bark of certain trees and is used in tanning leather. As 10 per cent of the leaf of tea consists of this substance it may readily be seen how easily improper methods of making tea will render it not a refreshing and delightful beverage but an actual poison to the digestive tract.

COFFEE

Like tea and chocolate, coffee also comes from a plant that can only be grown in the tropics. Its original home was in or near Arabia and its botanical name is Coffea arabica. There are, however, other species of the genus that produce coffee, but Coffea arabica is still its chief source. The plant is

FIG. 100.—COFFEE (Coffea arabica) The coffee beans are contained in a red berry.

FIG. 100.—COFFEE (Coffea arabica) The coffee beans are contained in a red berry.

now grown throughout the tropical world, but it does not thrive so well along the coast as it does at elevations of a thousand feet or so, where, in America at least, the best coffee is produced. The plant is a shrub or small tree, usually not over 12 to 15 feet tall, with opposite leaves and small tubular flowers, followed by a bright red berry, which contains the coffee “beans.” The flowers and berries are in small clusters in the axils of the leaves. Its use among the natives appears to date from time immemorial, but the Crusaders did not know it, nor was it introduced into Europe much before 1670. Its annual consumption is now well over two billion pounds, nearly half of which is used in this country. We use over ten pounds a year for each man, woman and child in the country, or nearly ten times the per capita consumption in England. Brazil produces over half the world’s total supply and consequently controls the coffee markets of the world. The plant was first brought into South America by the Dutch, who in 1718 brought it to Surinam. From there it spread quickly into the West Indies and Central America.

The coffee berries are collected once a year and spread out to dry, after which the two seeds are taken out. This is the simple method of all the smaller plantation owners, but a modern Brazilian coffee plantation follows a very different procedure. The berries are put in tanks of water, or even conveyed by water flues from the fields, and allowed to sink, which all mature berries will do. They are then subjected to a pulping machine which after another water bath frees the beans from the pulp. The former are still covered by a parchmentlike skin which, after drying of the beans, is removed by rolling machines. The coffee is then ready for export, but not for use until it is roasted. This is a delicate operation not understood except by experts, and should not be done until just before the coffee is ready to be used.

The average yield per plant is not over two pounds of finished coffee a year, but larger yields from specially rich soils are known. The plant is rather wide-spreading and not over five or six hundred specimens to the acre can be grown.

The so-called Mocha coffee is obtained in Arabia, where Turkish and Egyptian traders buy the crop on the plants and superintend its picking and preparation, which is by the dry method. Not much of this ever reaches the American markets, and the total amount of coffee now produced in Arabia, its ancestral home, is negligible.

CHOCOLATE

Unlike tea and coffee, chocolate is a native of the New World and was noticed by nearly all the first explorers. It grows wild in the hot, steaming forests of the Orinoco and Amazon river basins, although it was known in Mexico and Yucatan as a cultivated plant from very early times. By far the largest supply still comes from tropical America, although it is grown in the Dutch East Indies, Ceylon, and West Africa. It must have been cultivated for many centuries before the discovery of America, as scores of varieties are known, all derived from one species. This is Theobroma cacao, and both the generic and specific names are interesting. Theobroma is Greek for god food, so highly did all natives regard the plant, and cacao is the Spanish adaptation for the original Mexican name of the tree. Throughout Spanish or Portuguese-speaking tropical America the tree is always spoken of as cacao.

The chocolate tree is scarcely over twenty-five feet tall, has large glossy leaves and bears rather small flowers directly on the branches or trunk. This unusual mode of flowering, common in rain forests, results in the large sculptured pods appearing as if artificially attached to the plant. Each pod, which may be 6 to 9 inches long, contains about fifty seeds—the chocolate bean of commerce.

When the beans first come out of the pod they are covered with a slimy mucilaginous substance and are very bitter. To remove this the beans are fermented or “sweated,” usually by burying in the earth or piled in special houses for the purpose. After several days, sometimes as long as two weeks, the beans lose the mucilage, most of their bitter flavor and often change their color. After this they are dried and are ready for roasting, which drives off still more of their bitter flavor. Chocolate is made from the ground-up beans containing nearly all the oil, which is the chief constituent, while cocoa is the same as chocolate with a large part of the oil removed. As in tea and coffee, there is an alkaloid in chocolate for which, with its fat, the beverage is mostly used.

Very little chocolate is now collected from wild plants, and cacao plantations are important projects in tropical agriculture. Because of its many varieties, some nearly worthless, the business was rather speculative until a few good sorts were perpetuated. Much valuable work on this plant and the isolation of many good varieties has been done by the Department of Agriculture in Jamaica, British West Indies. Cacao plantations are usually in moist, low regions near the coast, preferably protected from strong winds, to which the plant objects. The trees are set about ten to fifteen feet apart each way and begin bearing after the fifth or sixth year. The young plants are always shaded, often by bananas, which are cut off as the trees mature. The tree will not thrive unless the temperature is about 80 degrees or more and there should be preferably 75 inches of rainfall a year, about twice that at New York. Chocolate-growing regions are apt to be unhealthy for whites, and native labor is practically always used. The business is very profitable, but still somewhat speculative.

3. Fibers

Not only do plants furnish us with food and drink, but most of our clothing is made from plant products. There is annually produced twice as much cotton as wool, while linen is made from the fibers in the stem of the flax plant, which is also the source of linseed oil. Fibers occur in many different parts of plants, but most often in the stem, or in the bark of the stem. Some occur in the wood itself, as for instance that in spruce wood, from which news paper is made. Others are found in the attachments of the seed, such as cotton. Some are very coarse, such as that of Carex stricta, a swamp sedge from which Crex rugs are woven. Others like that of the leaves of the pineapple are as fine as silk, and in the Philippine Islands where much pineapple fiber is produced, some of the most beautiful undergarments and women’s wear are made from it. Again, others, such as Manila hemp, furnish us with cordage of great strength.

COTTON

It has been stated, perhaps a little rashly, that the value of the cotton crop in our Southern States exceeds all other agricultural products of the country. Whether this be true or no matters not, as cotton production and manufacture is certainly one of the most important industries of the world. Our own New England mills and those in Lancashire total an enormous volume of manufactured cotton goods, and what the stoppage of the cotton crop means to these industrial centers was shown even so far back as the Civil War, when the “cotton riots” in Lancashire were noised all over the world. Cotton is the most important of all fiber plants.

There are several different kinds of commercially important cottons, and perhaps dozens of others, all derived from the genus Gossypium, a relative of our common garden mallows belonging to the Malvaceæ. By far the most valuable is Sea Island cotton, derived from Gossypium barbadense, which is probably a native of the West Indies, although really wild plants are yet to be discovered. It is the kind, of which scores of varieties are known in cultivation, that is grown mostly along our southeastern coastal States. Next in value, but cultivated in greater quantity because larger areas are suited to it, is Gossypium hirsutum. The fiber is a little shorter, but the total amount of cotton derived from this species probably exceeds that from all other kinds. It is the cotton grown mostly in upland Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas, and the wild home of this species is supposed to be America, although it, too, has never been found in the wild state. The third cotton plant is Gossypium herbaceum, a native of India, and the origin of many varieties now grown in that country. It has a shorter fiber and is worth about one-third the price of Sea Island cotton. From Abyssinia and neighboring regions comes the fourth important cotton plant, Gossypium arboreum, differing from the others in being a small tree. All the others are shrubby, while G. herbaceum is merely a woody herb. These different plants have been tried in the countries suited to cotton raising, but, generally speaking, the chief crop from each is produced in the country nearest the supposed wild home of it.

In all of them the fiber is really an appendage of the seeds, and each pod as it splits open is found to be packed full of a white cottony mass of these fibers with the seeds attached. These white masses of cotton, or bolls, have to be picked by hand, as no really successful machine has ever been found for this purpose. Women and children do a large part of the picking, and the wastage due to careless picking is tremendous. The whole value of the cotton crop depends upon an invention by Eli Whitney, an American, of a machine to separate the cotton from its seed. This “ginning” machine is now much perfected and, in America at least, is the chief method of separation of fiber and seed. In India and for certain other varieties a different type of machine, known as the Macarthy gin, is employed. The latter is used in America also for some of the long-fiber Sea Island cottons. With the baling of the cotton the work of the grower is over and the product is ready for the manufacturers. The resulting seed, after ginning, once little valued, is now an important plant product, cottonseed oil, cattle feeds, soap, cottolene, fuel oil, and fertilizers being derived from it. Its value in the United States now totals millions of dollars annually.

In growing cotton in America seeds are sown in April, and the beautiful yellow flowers with a red center bloom about June or July, followed in August by the pod. This splits open and is ready for picking by September and October. The plants are grown in rows four feet apart and are set one foot apart in the row. Clean cultivation is absolutely necessary, and in first-class plantations all weeds are kept out. The plant needs a rich deep soil.

HEMP AND CORDAGE

There are a variety of plants which furnish products known as hemp, but commercially only three are of much importance, the plant universally known under that name, the Manila hemp, and sisal. All of them are used chiefly for cordage.

The hemp of the ancients is a tall annual related to our nettles, with rough leaves, and a native of Asia. For centuries an intoxicating drink was made from the herbage of this plant, and this with the narcotic hashish, which is made from a resin exuded by the stems, obscured the fact that Cannabis sativa is a very valuable cordage plant. The coarse fibers are found in the stem, and these are cut and retted, the retting or rotting process separating the fibers from the waste portions of the stem. The fibers are so long and coarse that only cordage, ropes, and a rough cloth are made from them, but enormous quantities are raised for this purpose, especially in Europe. As hashish is now a forbidden product in many countries, due to its dangerous narcotic effects, the hemp plant is more cultivated for fiber than for the narcotic. But in the olden days hashish had a tremendous vogue in the Orient and was known at the time of the Trojan wars, about 1500 B.C. Fiber from the plant was almost unknown to the Hebrews, and it was not until the beginning of the thirteenth century that it came into general use. It is now probably as important as sisal, but not as Manila hemp, the most valuable of all cordage plants. The hemp is diœcious and the female plants are taller and mature later than the male. Two cuttings are therefore necessary in each field.

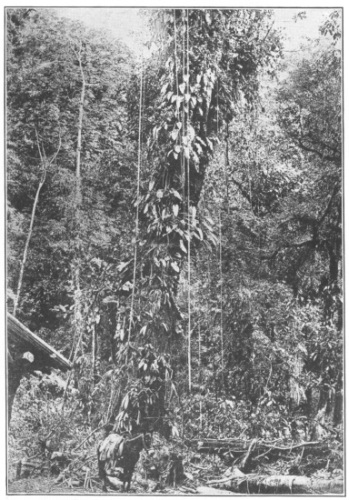

The Manila hemp is derived from a banana (Musa textilis), that is a native of tropical Asia and is much grown in the Philippines. While the fruits of this plant are of very little or no value, the fiber from the long leafstalk is the best cordage material known. Also the finer fibers near the center of the stalk are made up into fabrics, which are rarely seen here, but are said to be almost silky in texture. As a cordage plant, however, Musa textilis is now easily the most important, and from a commercial point of view the Philippine Islands is the only region to produce it in quantity. It has been tried with not much success in India and the West Indies. Methods of extracting the fibers are still very primitive, as it is nearly all scratched out by natives with saw-toothed knives made for the purpose. After the fleshy part of the leafstalk has been separated from the fiber this is merely put out on racks to dry. The finished product has so much value for large cords and ropes that the fiber makes up about half the total exports of the Philippine Islands. Its great strength may be judged from the fact that a rope made from it, only about one inch thick, will stand a strain of over four thousand pounds. No other fiber is anywhere near this in strength and yet of sufficient length to be of use as cordage. There are still thousands of acres suitable for its culture in the Philippines, but the extraction of the fiber awaits some inventive genius who will make a machine for that purpose. Many have tried, but so far the primitive scratching out by natives is the only method in use and it is admitted that it wastes nearly one-third of the fiber. The so-called Manila or brown paper is often made from old and worn-out ropes of Manila hemp, but, as in the case of cordage itself, adulteration with cheaper fibers is common.

From Yucatan, the Bahamas, and some other regions of tropical America comes the most valuable American cordage plant, known as sisal. The fiber is extracted from the thick coarse leaves of a century plant, known as Agave sisalina or Agave rigida, which looks not unlike the century plant so common in cultivation. The plant belongs to the Amaryllis family and is native in tropical America. Thousands of acres are planted to sisal in Yucatan and a machine for scratching out the fiber is in general use. The plant produces each year a crown of eight or ten leaves from three to five feet in height, each tipped with a stout prickle. Unlike the common century plant of our greenhouses there are no marginal prickles on the leaves of the sisal. After extraction the fiber is stretched out on racks to dry and is then ready for manufacture into rope.

JUTE

During the late war the Germans were reported to be sending flour and sugar to their armies pressed into large bricks for the want of bags to ship them in the ordinary way. Gunny sacks, or jute bags, as they are more often called, are made literally by the hundreds of millions, as practically all sugar, coffee, grains and feeds, and fertilizers are shipped in them. Jute is a tall herb, a native of the Old World tropics, but suitable for cultivation in many other tropical regions. Practically all the world’s supply now comes from India, probably because of the cheapness of labor rather than any peculiar virtue of the soil or climate of that country. The plant has been experimentally grown in Cuba with entire success, but labor conditions made cheap production of the fiber impossible.

The jute plant, known as Corchorus capsularis or C. olitorius, grows approximately six to nine feet tall and is an annual, often branching only near the top. They are not very distantly related to our common linden tree. At the proper maturity the whole plant is harvested and the stems are tied into bundles ready for the retting process. Of all fiber processes this is the most difficult, largely because no machine or chemical has yet been found to

The fiber is mostly derived from Corchorus capsularis and from Corchorus olitorius.

extract the fiber of jute, or flax, and this is accomplished by placing the stems in water, which rots out the fleshy part of the stem, leaving the fiber. Some notion of the difficulty of this task in such plants as jute is gained by realizing that over twelve million bales of finished fiber are produced each year, and that the retting may take from two days to a month. The retting process is aided by certain organisms of decay in the water, by the temperature, and by some other factors not yet understood. The process is allowed to go on only long enough to separate flesh from fiber, which makes frequent inspection of the bundles in the filthy water an absolute necessity. At the proper time the natives are able to split off the bark, which contains the fiber, from the stem, and while standing up to the waist in the water, he picks or dashes off with water the remaining impurities. The fiber is then dried on racks and subsequently, under enormous pressure, packed in bales of four hundred pounds each. An average crop would be about two and one-half bales from an acre of jute, so that in India there must be considerably over five million acres devoted to the cultivation of the plant. While for many years this tremendous output of fiber was sent to England for manufacture, power looms were set up in India about the middle of the last century. There are now over three-quarters of a million spindles there, and some jute is sent to the United States for manufacture here.

Next to cotton jute is probably the most important fiber plant in the world. For hundreds of thousands of people in India and in England it is the only source of livelihood. To the inventor who can eliminate or reduce the costly retting process of jute, or of flax, which goes through essentially the same operation, there is waiting a golden future, for it is largely the cheapness of labor and willingness of its natives to stand in the retting pools that has made India the jute region of the world.

Lack of space forbids mention of the many other fiber plants, some of which, like flax, are of large importance. Their fibers are used in a variety of ways and are found in different parts of the plant. A few of these, together with the names of the plants and the regions where they are native, are as follows:

| Native | Product | Name of Plant |

|---|---|---|

| Bowstring hemp. Sansevieria, several species. | Bowstrings and cordage. | Tropical Africa and Asia. |

| Coconut palm. Cocos nucifera. | Coir. | Tropical America (?) |

| Flax. Linum usitatissimum. | Linen. | Europe and Asia. |

| Kapok. Eriodendron anfractuosum. | Kapok, for stuffing. | India. |

| New Zealand flax. Phormium tenax. | Cordage. | New Zealand. |

| Paper mulberry. Broussonetia papyrifera. | Paper pulp in Japan. | Japan. |

| Pita. Bromelia Pinguin. | Pita fiber, fabrics. | Tropical America. |

| Queensland hemp. Sida rhombifolia. | Jute substitute. | Tropical regions. |

| Raffia. Raphia ruffa. | Cloth and for tying. | Madagascar. |

| Ramie. Boehmeria nivea. | Ramie cloth. | Tropical Asia. |

| Rattan cane. Calamus rotang. | Rattan, cordage, and coarse cloth. | India. |

| Rush. Juncus effusus.[2] | Matting in Japan. | North temperate regions. |

| Sedge. Carex stricta. | Rugs and mattings. | Northern North America. |

| Spruce. Picea rubens, canadensis, etc. | Paper pulp. | Northern North America. |

| Willows. Salix, many species. | Basketry. | Temperate regions mostly. |

No mention can be made here of the hundreds of fiber plants used by the natives of various parts of the world, some of them probably having great commercial possibilities. The extraction of these fibers by machinery or chemically will open up a large commerce in such plant products, the value of which is now unsuspected or ignored. While the value of cotton, jute, and Manila hemp is reckoned in the hundreds of millions, some of these native fibers are found in plants whose wild supply is almost inexhaustible, and some of which are quite as capable of cultivation as the better known fiber plants. Few fields of inquiry offer greater possibilities to the economic botanist than fibers.

4. The Story of Rubber

Along the north coast of Haiti, particularly near Cap Haiti and Puerto Plata, there are scattered a few plantations devoted to rubber growing; and it is not without interest that Columbus on his first voyage landed at about this precise spot in December, 1492, and found the natives playing a game of ball made of rubber. He wrote: “The balls were of the gum of a tree, and although large, were lighter and bounced better than the wind balls of Castile.” This is apparently the first notice of the use of rubber, a substance now of world-wide importance, and derived from many other plants than the tree mentioned by Columbus. This is Castilla elastica, a native of certain islands of the West Indies and the adjacent mainland, and a relation of our common mulberry.

For over three centuries rubber, or caoutchouc as it was often called, was only of very casual use before the process of vulcanizing was discovered by Charles Goodyear, an American, in 1839. This combination of rubber with sulphur transformed a material much subject to heat and cold, and of almost no manufacturing value, into one from which hundreds of articles of daily use are now manufactured. Previous to this it had been used mostly, and in fact almost exclusively, as a waterproofing material for cloth, a process much developed by the firm of Charles Macintosh & Co., who appear to have taken out the first patent for a waterproofing process in 1791, in England. The rubber tree found by Columbus is still grown in considerable quantities and is a valuable source of rubber, but it has been greatly overshadowed by a Brazilian tree which now produces over two-thirds of all the rubber in the world.

FIG. 102.—BRAZILIAN OR PARA RUBBER (Hevea brasiliensis) Native in the Amazon region, but now much grown in the East Indies.

FIG. 102.—BRAZILIAN OR PARA RUBBER (Hevea brasiliensis) Native in the Amazon region, but now much grown in the East Indies.

This Brazilian tree, a native of the rich rain forests of the Amazon, is Hevea brasiliensis, and a relative of our common spurges of the roadsides and of the beautiful crotons of the florist, all belonging to the family Euphorbiaceæ. The first important notice of this rubber appears to be by the astronomer C. M. de la Condamine, who was on an astronomical trip to the Amazon in 1735. He described Para rubber, as it has since been called, and by 1827 the export of this gum had grown to 31 tons a year. In 1910 Brazil exported over 38,000 tons, nearly all of which was collected from wild trees. After the discovery of vulcanization the demand for all kinds of rubber increased by leaps and bounds and it became obvious that the wild trees, although tapped regularly, would not supply all of the necessary amount. For years the Brazilian Government protested the export of seeds or other means of growing the plant out of the Amazon, but in 1876 H. A. Wickam chartered a steamer and loaded her with 70,000 seeds of para rubber trees and some crude rubber, and had the ship passed by the Brazilian port authorities as loaded with “botanical specimens.” He safely transported the cargo to the Kew Gardens, London, where only about 4 per cent of the seeds ever germinated. From there the young plants were sent to India, where now, and in the Straits Settlements and the adjacent islands, there are huge plantations of para rubber. From the wildest speculation in rubber shares on the London Stock Exchange, which followed the successful introduction of the plant into British possessions, the industry has now settled down to be one of the most profitable in plant products of the East.

The rubber of both Hevea and Castilla is produced from the milky juice or sap of the trees and is actually a wound response. As the trees are tapped the latex, as the milky juice is called, runs out of the wound and upon reaching the air coagulates. This material is removed and a new wound made, a process which is repeated for several years. There is still work to be done upon the problem of how often plantation trees should be tapped to get the greatest flow of latex without injuring the tree, but in many plantations it is done every day or every other day in the season, some rubber planters allowing a resting period during leaf fall, others again tapping almost continually. The actual wound is made by removing just enough bark to induce a flow of latex, but not until the wound is completely healed, a process taking from four to six years, can that particular part of the bark be cut again. With almost daily tappings the problem of finding fresh pieces of bark into which the cut may safely be made has been developed into a fine science. In the wild trees of Brazil it is still done by natives, probably rather wastefully. Rubber plantations in the tropical regions of Asia now total over a million acres, as compared to only slightly over 200,000 acres in the American tropics and from all other non-Asiatic sources. Of this probably 100,000 acres are in Africa. At the present time nearly half the world’s supply of rubber comes from these plantations, the balance still coming from Brazil.

There are two other rubber-producing plants, neither of which are as important as Hevea and Castilla. One is the common rubber plant so much grown as a house plant and said to be much cherished for that purpose in Brooklyn. It is a kind of fig tree, known as Ficus elastica, a native of India and the source of India rubber. It was used for years, before the days of vulcanization, mostly for lead-pencil erasers. Thousands of acres of it in India were recently destroyed to make room for Hevea, although it still produces a respectable amount of rubber, inferior, however, to Hevea and Castilla. In Mexico a new source of rubber is the guayule rubber plant, a small shrub native of the drier parts of the Mexican uplands. It does not produce latex, as practically all other rubber plants do, but particles of rubber are found directly in its tissues, mostly in the bark. While of some importance, this shrub, known as Parthenium argentatum, a member of the Compositæ or daisy family, is not likely to become a dangerous rival of either Para or Castilla rubber. Wild sources of guayule rubber are already reported as diminishing rapidly, so that its permanent success will depend upon cultivation. At least a score of other plants are known to produce rubber of a kind, but none of them have yet been much developed. From most plants with a milky juice, such as dogbane or spurge, rubber of some sort can usually be recovered. The production of this substance is directly due to a response of the plant to wounds, and there are still great fields of research necessary on this phase of plant activity, upon which a great industry has already been built.

5. Drugs

Nearly all the drugs and medicines of importance are of vegetable origin, and from the days of Theophrastus the study of plants as possible medicines has been one of the chief phases of botanical research. In the early days all that was known about plants was learned by men interested in medicine, and some of their quaint old books are interesting relics of a bygone day. At present, pharmacognosy, or the science of medicinal plant products, is a highly developed specialty taught in medical and pharmacy schools. And yet the greatest medical college in this country has recently issued instructions to its staff of doctors and nurses to pay particular attention to “old wives’ remedies,” most of which consist of decoctions of leaves and other parts of plants. They have done this because all the knowledge of the scientists regarding medicinal plants has its origin in the habit of simple people turning to their local plants for a cure. The accumulation of the ages, aided and guided by the scientist, has resulted in the wonderful things that can now be done to the human body through the different drugs, nine-tenths of which are of plant origin.

There is almost no part of a plant that, in some species at least, has not been found to contain the various acids, alkaloids, oils, essences, and so forth, which make up the chief medicinal or, as the pharmacists call it, the active principle of plants. In certain of them the most violent poisons are produced, such as the poison hemlock which killed Socrates, and the deadly nightshade. And again the unripe pod of one plant produces a milky juice so dangerous that traffic in it is forbidden in all civilized countries, and yet later the seeds from that matured pod are sold by the thousands of pounds to be harmlessly sprinkled on cakes and buns by the confectioners. Earlier in this book it was said that plants are chemical laboratories, and nowhere has this alchemy been carried to such a pitch of perfection as in the hundreds of drugs produced by different plants. Reference to special books on that subject should be made by those interested, as only a few of our most important drug plants can be mentioned here.

QUININE

The Spanish viceroy of Peru, whose wife, the Countess del Chinchón, was dangerously ill of a fever in that country about 1638, succeeded through the aid of some Jesuit priests in curing the malady, with a medicine which these priests had gotten from the natives. It was a decoction from the bark of a tree, and its fame soon spread throughout the world as Peruvian bark. Even in those days malaria was the curse of the white man in tropical regions, and since then it is hardly too much to say that the discovery of this drug has made possible for white colonists the retention of thousands of square miles of tropical country that without it would in all probability be unfit for occupancy. To the natives, too, quinine has been one of the greatest blessings, and in some of the remote regions of the tropics the writer has found quinine more useful than dollars in getting help from fever-ridden natives, too poor and too remote from civilization to get the drug.

For more than a hundred and fifty years after the discovery of Peruvian bark it was always taken as a liquid, usually mixed with port, and an extremely noxious and bitter drink it made. The fine white powder which we now use in tasteless pellets or pills has made the drug even more useful than before.

The trees from which the bark is used all belong to the genus Cinchona, named for the first distinguished patient to benefit by it, and belong to the Rubiaceæ or madder family. There are at least four or five different species. For many years Peru and near-by states were the only source of the bark, and the English became convinced that the great trade in the drug would exterminate the tree, so in 1880 they introduced the plant into India. These cinchona plantations now provide most of the world’s demand, and some idea of what that means may be gleaned from the fact that in Ceylon alone over fifteen million pounds of the drug are produced annually. In India itself the plantations are largely government owned and quinine is sold in the post offices at a very low rate. In cinchona plantations strips of the bark are removed, and after a proper period of healing, the process is repeated. It takes about eight years before it is safe to begin cutting the bark.

ACONITE

Most doctors use aconite for various purposes and it is mentioned here chiefly as illustrating a common characteristic of many medicinal plants. The whole plant is deadly poisonous, and in the root there appears to be a concentration of this poisonous substance, which makes the plant one of the most dangerous known. All of the drug aconite is derived from Aconitum Napellus, a monkshood, belonging to the buttercup family. It is a perennial herb with beautiful spikes of purple-blue flowers, not unlike a larkspur, and is a native of temperate regions of the Old World. A related Indian species has been used for probably thousands of years by the natives. They poison their arrows with it and so deadly is the drug that a tiger pricked by such an arrow will die within a few minutes. It is conceded to be the most powerful poison in India. Numerous accidents have resulted in Europe from careless collectors of the roots of horseradish, who sometimes get aconite roots mixed with that condiment, usually with fatal results.

So many other plants are violently poisonous, and yet yield the most valuable drugs, that the greatest care has to be used in their collection and preparation. The habit of many children of eating wayside berries should be discouraged, as some of our most innocent-looking roadside plants are actually deadly if their fruits or foliage are eaten. Fortunately only a very few plants are poisonous to the touch, notably poison ivy and poison sumac, and some of their relatives.

OPIUM AND MORPHINE

Almost no plant product has caused more misery and relieved more pain than the juice of the unripe pod of the common garden poppy, Papaver somniferum. From it opium is extracted, the chief constituent of which is morphine. If tea can be said to have precipitated our war of independence, opium was indirectly the cause of the opening of China to the western world. The degrading effects of opium had become so notorious that the Chinese in 1839 destroyed large stocks of it, mostly the property of British merchants, and prohibited further importations. In the subsequent negotiations which ended in war, China was opened up to trade. No civilized country now openly permits the sale of opium, although there is still a good deal of it used in practically all parts of the world. The effects of lassitude, subsequent ecstasy, and stupefaction are due to an alkaloid, the continued use of which forms a drug habit of serious consequences. Parts of China, Turkey, Persia, and Siam are said to be still large users of opium which is chewed, or more often smoked. Until comparatively recently fifteen out of every twenty men in some of these countries were regular users of the drug. The legitimate use of morphine by physicians has done more than almost anything else, with the possible exception of cocaine, to relieve suffering, and there is consequently a considerable trade in the drug.